On March 9, the year of our Lord 2018, Mr. Mathers and I traveled to the Royal Infirmary at the Edinburgh University campus to run a Thinkathon hosted by the Usher Institute. The night before we had prepared ourselves with a thorough review and copious discussion of the Agenda. We had prepared. The way to the infirmary was an adventure in and of itself, and Mr. Mathers and I became lost in a forest and had to traveled over a mountain and a stream before we were spat out at the bottom of a set of stairs that led to Building Nine. The stairs, of course, were closed by construction and we had to find another way around to the ominous glass protrusion overlooking the University Hospital and various medical facilities. We felt the cameras turn in our direction as we wandered towards the entrance.

“Is this a trap?” I asked.

We found our way to the entrance and were greeted by an excited woman, Kathryn, our host. Today we would be facilitating a discussion between medical professionals / academics and the industry on Patient Generated Health Data, specifically, the challenge of integrating this data in a way that is helpful to clinicians. Specialists in interoperability in Health IT, medical informatics, health sciences, digital health data and commercial research around healthcare related products were in the room. Bryan and I didn’t have much (any) domain knowledge here, but we were able to play advocates for patients as well as data privacy and open source specialists.

As the day unfolded I would feel the lack of support from the open source and privacy activist community in the conversation. Here we were, talking about something that affects every man, woman and child on the face of the Earth — innovation and advancement of the healthcare industry using all the power of technology — and we were just eleven people in a room. The questions and concerns we began to address were not technical problems, as is so often the case. They were social problems, and they had to do with how we take care of each other.

Setting the Scene

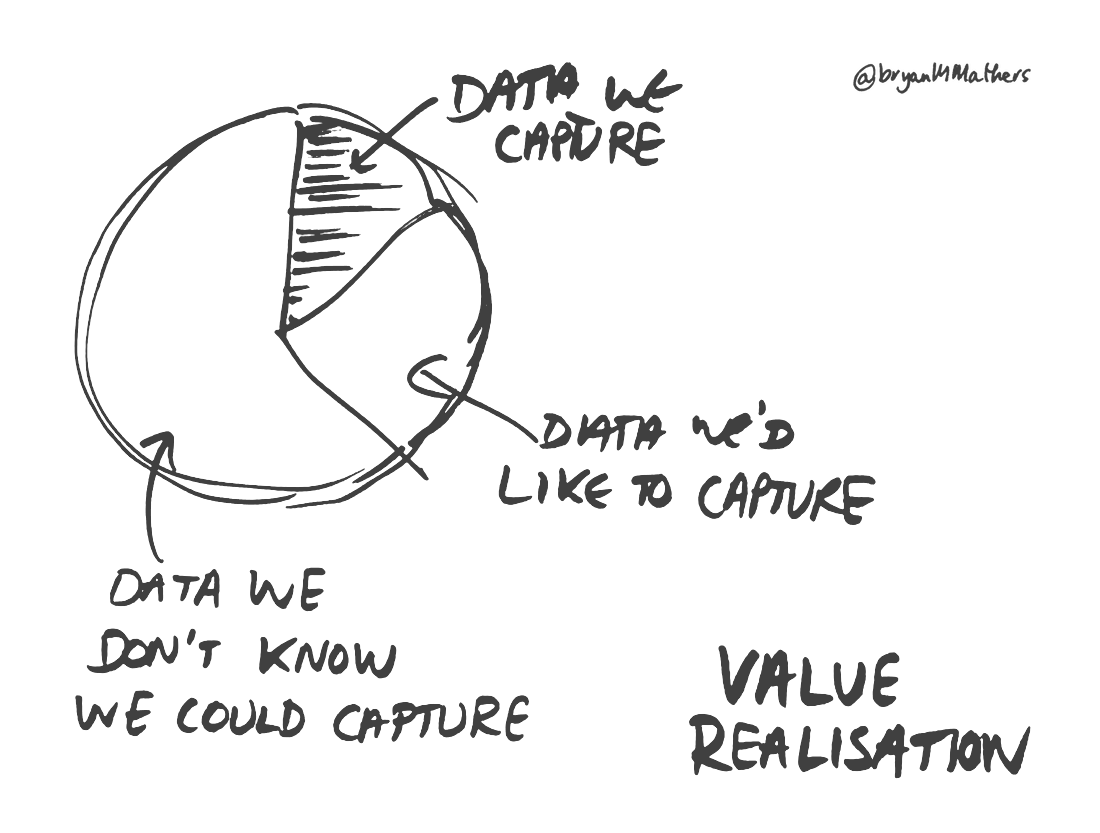

We started the conversation by asking the participants to help us understand the issue from a meta level. Clinicians have a very different view of a patients health because they have an episodic view — a patient goes to the doctor when something feels wrong. A patient, on the other hand, has a more complete view, but may be lacking the expertise to either diagnosis pre-existing health problems or the ability to avoid them. 99.99% of prevention is self-care. Clinicians cannot possibly know the complete picture of every patient and patients do not want to share the complete picture in most cases anyway. There is a tricky tension between what the clinicians know about a patient and what they are expected to know. And there is a tricky tension between what sorts of information is meaningful and what can be captured.

Defining the Cast

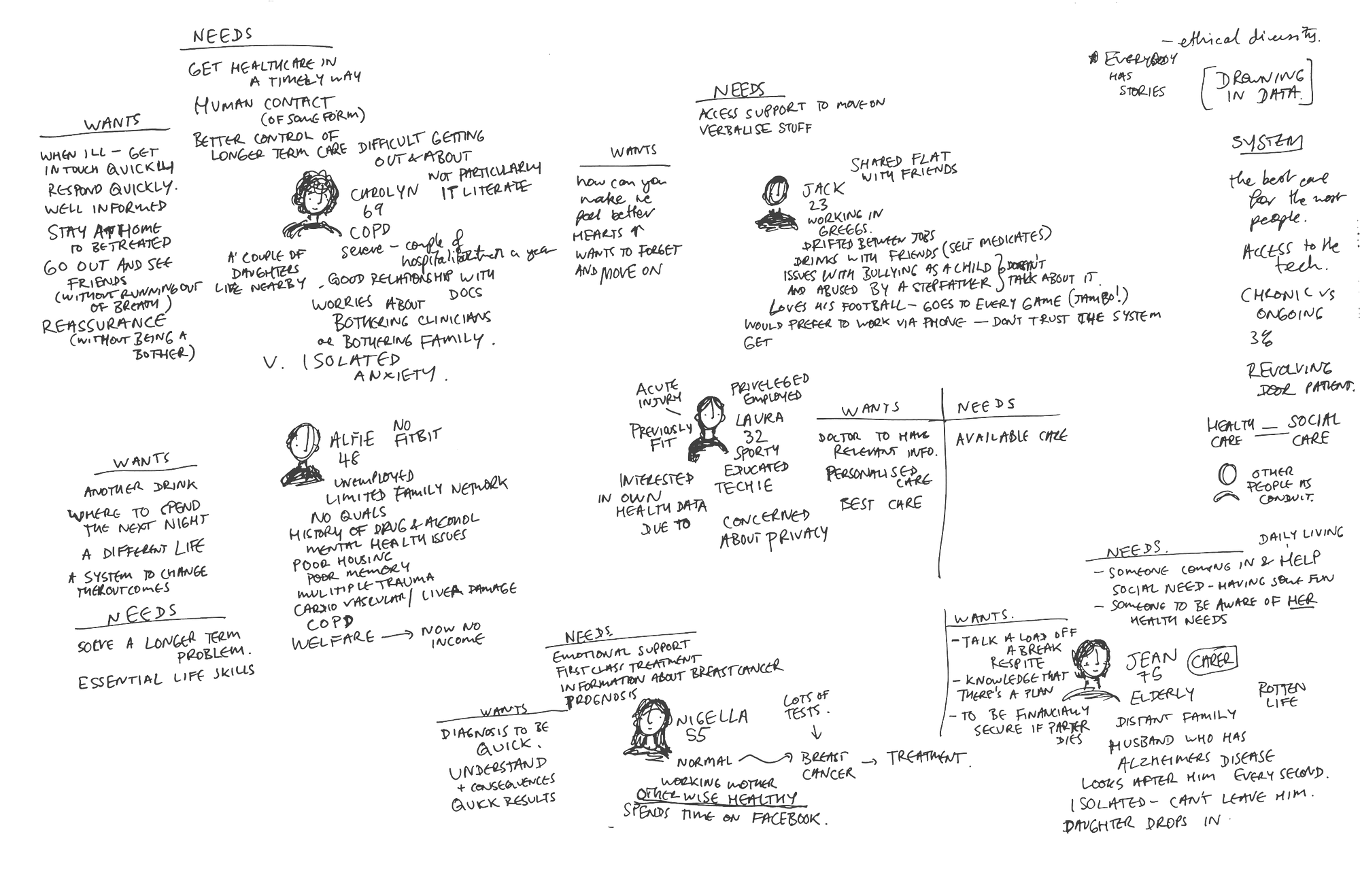

Once we spent a few minutes talking about the overarching topic, we dove into an exercise we find extremely useful in sussing out the minute details of big problems. It’s important to understanding the “users” and focus in on what actual people need and want. What are their concerns? What would they be willing to do? To do this, we facilitated a persona building exercise and asked participants to talk about different patient types that they were trying to help. In this conversation, because healthcare is part of everyday life for all people, it was important to try and narrow the field so we could have a conversation that felt productive. There will always be outliers, but a persona exercise can help you cover large swaths of the population in a targeted way.

We met a number of characters:

Carolyn, a 69 year old mother of two with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is not particularly tech literate, but she, like everyone, has a smartphone. Carolyn has been hospitalized a couple of times in the past year, and she has a good relationship with her doctors. She worries, however, about bothering her caretakers and her children with her health problems. She’s is therefore quite isolated and has a lot of anxiety. Carolyn needs access to healthcare in a timely way, she needs some human contact and she needs to have better control over her own long term care. Carolyn wants to be treated at home as mobility is an issue for her, she wants to have quick response when she is ill and she wants to be able to get out and see friends at some point. She wants reassurance that she is not a bother.

The Problem Spaces

Through the conversation about our cast, a number of different issues emerged that make gathering, processing and utilizing patient generated health data challenging.

Privacy from the perspective of Health Care

One of the biggest issues we ran into was around privacy. Indeed, our perception and understanding of privacy needs to be reflected upon in general, what with all the data flying around about us. How is healthcare data any different? Well, traditionally healthcare has been one of the most private industries because it is a sensitive topic to most people. Health care data is locked down and siloed. No one wants to take more responsibility for holding patient information than they absolutely have to. Patients want to pick and choose what they share with whom. Anonymity about certain things is required…indeed, privacy around health data is a complicated matter.

Data means what to whom?

A lot of our discussion pointed to the fact that the medical industry needs to humanize data and help patients understand what’s needed. Indeed, at one point I role-played a typical patient and started talking about my fitbit data. A doctor in the room interrupted and said “I don’t care about your fitbit data at all!” I found this interesting because to me it seems that fitbit data might show a particular level of activity. I am more or less active. The clinician, however, argued that this will be clear in other ways and that pouring more useless data at him actually causes harm — it requires more of his time and clinicians are already stretched thin in our burgeoning population. Patients don’t understand what a clinician might need and don’t know how appropriate their self collected data might be. There’s also the issue of research data, which might be a different kind or amount of data that becomes relevant.

Data Structuring and Vendor Lock in

And then there is the unfortunate occurrence of vendor lock-in in the medical industry (just as schools tend to teach the Microsoft products Word and Excel because of legacy decisions, so too does the medical industry suffer from bad interoperability between various systems. Many of the products in use have bad UI, never improved nor replaced as tight budgets made upgrading to a new, more usable software (and hardware!) low priority in an industry that deals with life and death. Clinicians have multiple logins that cost precious minutes, and formats of scanned medical records are not searchable and data exports are often non-searchable formats as well.

Moving forward

There is a constant tension between story and information when it comes to utilizing patient generated health data. The lack of up-to-date records and the lack of economic structures which support prevention* are keeping health care in the twentieth century. We can and have to do better.

We need ways to create cyclical information transfer to help lessen the burden of clinicians. How can we send patient generated health data to a clinician to AI and back to the patient without creating more work or a system that could endanger someone’s life? It’s a big question, one that deserves a wider audience.

My advice would be to break free from the secretive silo of medicine and reach across communities. There are other people who would be useful in this conversation. Use tactics from organizations who are great at demanding change. Get advice from privacy advocates. Open the conversation and help the public understand these complicated issues. Then propose solutions see what people think, iterate, rinse, repeat.

Using open practices can help solve big social problems. Improving health care for the twentieth century is exactly the type of thing that open can help with.

* Surprise! Capitalism proves to be a huge problem for health care…

Useful resources

We had an interesting time hanging out with what could be a community destined to advance the Scottish medical industry.

I dug up a few resources around community building, facilitation, open source and the like to help this group move forward. At http://laurahilliger.com searching for things like “community” or “MOOC” will bring up tried and true strategies and reflections that I’ve used to generate knowledge, coalesce ideas and bring people together. For example, this post about cMOOCs could be a useful strategy in taking this work forward…

https://www.laurahilliger.com/?s=community

https://www.laurahilliger.com/?s=mooc

I have a library of facilitation materials here: https://laurahilliger.github.io/learning-materials/

My presentations, talks, slides: http://laurahilliger.github.io/presentations/

Finally, a particularly applicable and specific couple of resources. I write for opensource.com and am an Ambassador for the open organization. Our community has done a number of things that can help any group build a community. My all-time favorite strategy is the community call, for which I’ve written this guide.

Also, the Open Decision Framework (see my remix for Greenpeace) and the Maturity Model. This can help you think about what “open” means in your specific context.