1.6.1 Defining Web Literacies: The Semantic Argument

There have been numerous studies which examine the nuances between differing definitions of so-called new literacies (Pinto, Cordon, & Gomez Diaz, 2010). Since the first use of the term “information literacy” in 19741 (Pinto et al., 2010), varying terminology has been used to define the ability to find, analyze and use information in a changing knowledge landscape (Pinto et al., 2010). In recent years, many academics have added a social and cultural layer to the definition of these literacies.

Terminology used for these literacies include “information literacy”, “digital literacy”, “technological literacy”, “computer literacy”, “media literacy”, “communication literacy”, “internet literacy” and other ambiguous terms. As Doug Belshaw points out in his doctoral thesis (2011), these terms “do not have the necessary explanatory power, or they become stuck in a potentially-endless cycle of umbrella terms and micro literacies,” (p. 200). Belshaw makes an impressive case for ditching the semantic argument and focusing on the improvement of educational practice. He also suggests that the term “literacy” is too binary and that in the context of any digital or web skills the plural “literacies” should be used to show that in these realms there is no literate or illiterate, but rather degrees of literacy (Belshaw, 2011).

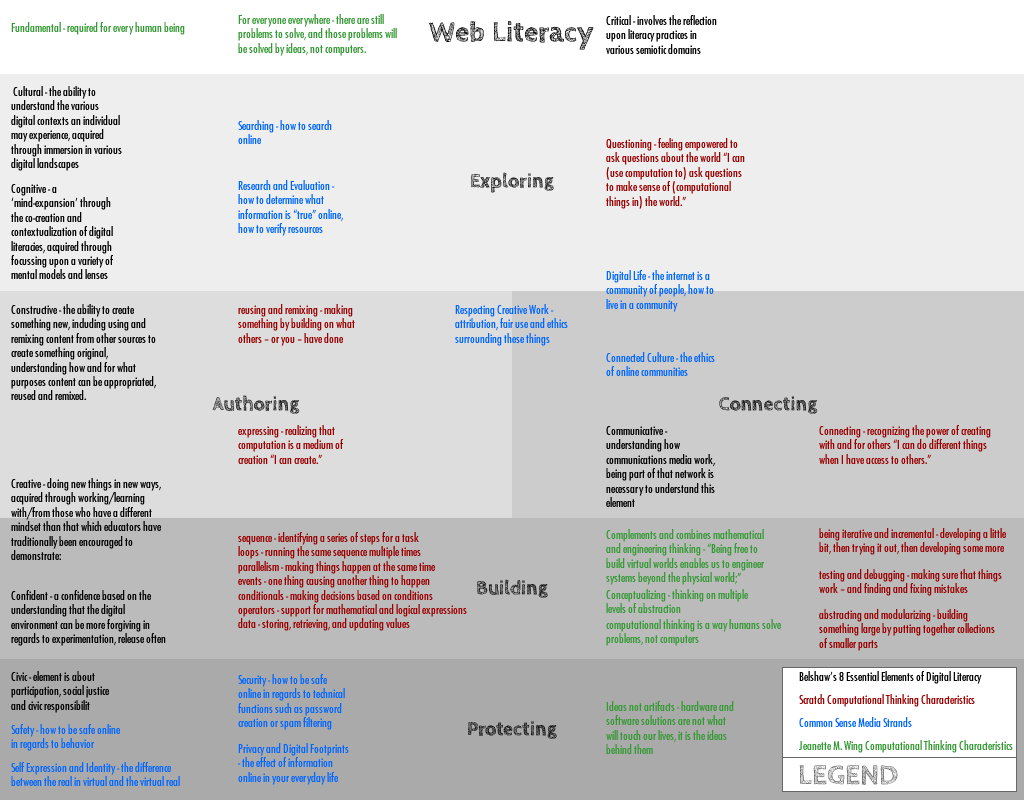

Through a pragmatic comparison of various definitions of these terms, Belshaw identified eight essential elements of digital literacies. Those elements are, as Belshaw defined them:

1. Cultural – the ability “to understand the various digital contexts an individual may experience […] acquired through immersion in various digital landscapes” (p. 207).

2. Cognitive – a “‘mind-expansion’ through the co-creation and contextualization of digital literacies,[…] [acquired through] focusing upon a variety of mental models and lenses” (p. 208).

3. Constructive – the ability to create “something new, including using and remixing content from other sources to create something original […], understanding how and for what purposes content can be appropriated, reused and remixed.” (p. 208-209).

4. Communicative – “understanding how communications media work” (p. 209), being part of that network is necessary to understand this element.

5. Confident – “a confidence based on the understanding that the digital environment can be more forgiving in regards to experimentation” (p. 211), the understanding of how releasing often is beneficial to your own work.

6. Creative – “doing new things in new ways” (p. 212), acquired through working/learning with/from those who have a different mindset than that which educators have traditionally been encouraged to demonstrate.

7. Critical – “involves the reflection upon literacy practices in various semiotic domains” (p. 213).

8. Civic – “element is about participation, social justice and civic responsibility” (p. 212).

Based on the work of Howard Gardner and the GoodPlay Project, Common Sense Media developed Digital Literacy and Citizenship curriculum containing nine strands that adheres to common core standards (Grayson, 2011). The curriculum is offered as an open educational resource2 (Grayson, 2011). The strands are:

1. Safety – how to be safe online in regards to behavior

2. Security – how to be safe online in regards to technical functions such as password creation or spam filtering

3. Digital Life – the internet is a community of people, how to live in a community

4. Privacy and Digital Footprints – the effect of information online in your everyday life

5. Self Expression and Identity – the difference between the real in virtual and the virtual real

6. Connected Culture – the ethics of online communities

7. Respecting Creative Work – attribution, fair use and ethics surrounding these things

8. Searching – how to search online

9. Research and Evaluation – how to determine what information is “true” online, how to verify resources

Interestingly, Dr. Belshaw’s eight essential elements are skills that do not necessarily have to relate to the World Wide Web, whereas Common Sense Media’s strands, with an exception of “Respecting Creative Work”, are exclusively in relation to the online space. Looking at the two sets of computational thinking characteristics from Jeanette Wing (2006) and Scratch (2011) reveals a similar pattern. Scratch uses specific computational concepts and practices, augmenting with three slightly more meta-level perspectives as their characteristics, while Wing defines computational thinking at a more meta-thinking level.

Web literacies are specific to the world wide web. The technical components as well as inherent social and cultural components of it, combine essential elements into a “digital literacy”. The definition of web literacies used in this thesis collapses Belshaw’s eight essential elements, Common Sense Media’s digital literacy and citizenship strands, Scratch’s computational thinking connections (Brennan et al., 2011) and Jeanette Wing’s computational thinking characteristics (Wing, 2006) into five overarching categories (see Figure 4). The five categories were initially created by Michelle Levesque of the Mozilla Foundation and are being defined at the macro-level in this thesis.

Web literacies are fundamental to every human being and involve critical thinking at every level. They are for everyone, everywhere. As Jeanette Wing (2006) put it,

“Computers are dull and boring; humans are clever and imaginative. We humans make computers exciting. Equipped with computing devices, we use our cleverness to tackle problems we would not dare take on before the age of computing and build systems with functionality limited only by our imaginations” (p. 35)

Figure 4: Categorizations of digital literacy and computational thinking characteristics from Belshaw, Scratch, Common Sense Media, and Wing into five overarching categories originally established by Levesque.

The five categories and the overarching definition for each level are:

1. Exploring – The cognitive and affective abilities needed to navigate and understand the community, culture and digital life. The World Wide Web offers and provides opportunity to use various digital spaces to learn about, question and evaluate human perceptions and actions.

2. Authoring – Being expressive, creative and constructive on the World Wide Web while articulating individual thoughts in the global, digital exchange of methods and resources and respecting the creative work of others.

3. Connecting – Communicating about and networking in digital life while participating in a respectful manner. Recognizing and adhering to the ethics of online communities.

4. Building – Confidently and creatively attempting to solve technical and social problems through incremental and iterative approaches. Using the ability to think on multiple levels of abstraction and modularization to develop material.

5. Protecting – Safely and securely participating in self-expression and civic duties in the Information Age. Understanding that the protection of the World Wide Web as a free and open public resource is a civic responsibility and the affective ability to claim solidarity for protective actions.

These elements have been considered in the definition of a webmaker, a term designating a degree of web literacy.

1.6.2 Other Definitions

Webmaker

A webmaker is an individual who has the cognitive capacity to understand the cultural landscape and technical mechanics of the internet. She actively participates in the contribution to knowledge networks on the World Wide Web. She possesses the social and technical skills to creatively and confidently submit new and unique perspectives into the ecosystem.

A webmaker has the ability and desire to explore the World Wide Web, author content, connect with various communities, build using code and protect the open infrastructure of the World Wide Web. She can search for and find the information she is looking for, and she can be critical about the information she accesses.

Hack/Hacking

Although the word “hack” has negative connotations, the Open Web community uses it in a positive context. To “hack” something is simply to take something that already exists and change it to make something new. A person can hack physical things – like board games – or a person can hack the web. Hacking has always been a key element in the creative process. It is a constructive collaborative activity, not a destructive one (Hacker Ethic, n.d.).

Remix

A remix is a derivative art form. In the web context, this term is used to imply that a new work is built off an already established base. The “base” work might refer to a code base, a curriculum base, an image base, a text base, etc.

Instructor/Teacher/Facilitator/Educator/Mentor

In another attempt to avoid a semantic argument, it is necessary to explain that in this thesis there are various terms used to designate informal and formal teachers, the target audience for the educational concept proposed within. These terms are interchangeable and should be considered synonyms.

Badges

The assessment approach used in this educational concept aims to give recognition for granular skills and overarching concepts in the form of badges.

“A ‘badge’ is a symbol or indicator of an accomplishment, skill, quality or interest. From the Boy and Girl Scouts, to PADI diving instruction, to the more recently popular geo-location game, Foursquare, badges have been successfully used to set goals, motivate behaviors, represent achievements and communicate success in many contexts.” (Knight, 2011)

1 Coined by Zurkowski in the paper “The Information Service Environment: Relationships and Priorities (Report ED 100391). Washington DC: National Commission on Libraries and Information Science.