Originally posted on Opensource.com

Want to overcome your team’s feelings of inadequacy? Start by making different language choices.

Recently I facilitated a creative work week for my colleagues working on the Planet 4 project at Greenpeace. One evening, when we came together in a closing circle after a day of intense creative work, I asked the participants to share how they were each feeling about the day. We allowed these reflections to manifest into conversation.

A concern surfaced: The task of creating a new ecosystem of sites for Greenpeace became, for a moment, completely overwhelming.

“Are we the right people to be doing this?” someone said.

That sentence hit me hard. It expressed the feeling that we shouldn’t be in the position we’re in.

It expressed a kind of impostor syndrome.

At Opensource.com, we’ve published several articles about impostor syndrome, which (as Nicole Engard notes in her piece, according to the Caltech Counseling Center) “can be defined as a collection of feelings of inadequacy that persist even in face of information that indicates that the opposite is true.”

In this particular case, however, multiple people were feeling impostor syndrome—not necessarily of themselves, but as part of their collective relationship to a project. This put a new spin on how open leaders might think about and ultimately address this phenomenon with their peers and teams.

How should we think about impostor syndrome when we aren’t talking about how a single individual might be feeling inadequate? What if, instead of someone saying “I don’t think I’m the right person for this team,” an entire team is expressing, collectively, that “We are not the right people to be doing this” What might make a group of people feel collectively inadequate?

Collective inadequacy?

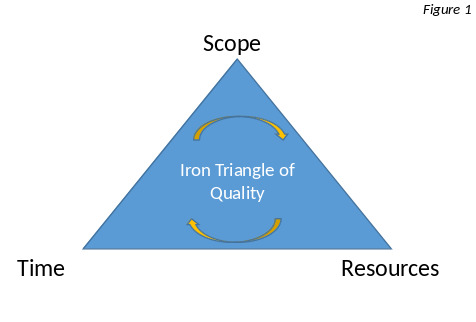

Perhaps we can relate this collective inadequacy to a version of the Iron Triangle:

Image courtesy of Brook Manville (CC-BY-SA)

Very rarely is a project perfectly scoped, perfectly timed, and perfectly resourced. The Iron Triangle isn’t just a theoretical framework of how a project runs; it’s also a mechanism to understand how the project team might be feeling. The language we use to talk about the sides of this triangle are related to the emotional well being of a team.

Talking about expectations

If the expectations for (or “scope” of) the project feel unachievable, a group of people may begin to feel overwhelmed or inadequate. Often in the social justice realm, for example, we talk about “changing the world” and “mass mobilization” and “shifting cultures” or “changing the public perception.” We tell people we are going to create a world where everyone is equal and diversity reigns supreme and openness will become the default setting. We write project manifestos and briefs that proclaim the ultimate mission of an organization, and we ascribe project goals to this mission with little regard for the contingencies a project will inevitably have. Our language indicates that we’re intending to create a complicated, multifaceted, systemic shift.

These aren’t SMART goals; they’re wild and unrealistic speculations. They overstate the impact a single project is going to have on a system. Of course, some projects can actually cause instant shock to a system—things that change the course of history immediately. But I can’t think of one off the top of my head (even the lightbulb took time to become a pervasive technology). A variety of factors go into creating systemic change, and a single project isn’t going have instantaneous effects on a larger system.

Even if the deliverables for a project are well defined, these lofty expressions can make it feel like the scope is bigger than it actually is. When developing briefs and project manifestos, or when talking to new hires or teammates about the project, try to think seriously about the words and phrases you’re using. A description that misrepresents a project or product’s scope might lead a future team to reel at its ambition.

Resourcing language

Another place where ambition needs to match reality and feasibility is in the area of resourcing.

People and money are two basic types of resources. In both cases, the words we use to describe our resources might create feelings of inadequacy.

I’m definitely guilty of calling my peers and colleagues “rockstars,” “brilliant,” and “genius,” and I’m not going to suggest that positive semantics should be left out of group discussions. However, we should consider constructions that may serve to reinforce unattainable expectations. Use consideration when speaking on behalf of a teammate or the team itself. Statements like “Oh, I’m sure we can do that; Amy is a rockstar” place an intimidating expectation on Amy that she hasn’t had the opportunity to digest. Likewise, claims like “We’ll pull an all-nighter” might create a tension point between the team and an individual who is unable to pull said all-nighter.

The same is true for how we talk about money. If you’re holding a project’s purse strings, and you actively remind your team that “a lot of money is on the table,” then you’re not helping. No one is striving to go over budget; it might be best to shield some or all of the team from budgetary concerns so that they can just do the work.

While a team might actively strive to create a positive working atmosphere through the language it uses to describe what it’s doing, occasionally positive feedback from outside the core team is necessary for dispelling feelings of inadequacy that might be gathering. You can become a resource to your colleagues. When people feel like no one notices them working hard, feeling like what we do matters becomes more difficult. So be the person who spends an hour every week looking into another team’s project, and tell that team something you like about the work they’re doing. Thank them for contributing to the greater good.

Talking time

Time is a human construct, and deadlines are mostly arbitrary. When leading a team, strive to be fluid and adaptable with your expectations for how long it takes to do anything and use language that helps people feel adequate.

No team knows what events are going to throw the project off its timetable, and no one misses a deadline on purpose. Of course, we need to be accountable to one another and live up to our commitments, but we should be aware at how we talk about time in relationship to our projects.

Asking your team “When do you think you’ll have that done by?” is a good example of a positive semantic relationship with time. This question is very different from “When will that be done?” or “We need this by date X.” Asking your team to give an assumption of finish-ability instead of a commitment to it allows the team to see the deadline as slightly flexible, which it should be. This creates accountability, puts the power in the team’s hands, yet doesn’t create a potential pressure point. At the end of the day, every project can take an extra day.

There’s also a difference between asking “Why isn’t that done yet?” and “Is there something blocking you?” The lizard brain will interpret the first phrasing as threatening as if you expected something long ago. When we’re threatened, the brain tells our bodies to release chemicals and electrical signals that cause stress and tension. The second phrasing activates no such threat because it uses neutralized language to ask about the status.

Listen to yourself

We all know that what you say can directly impact someone’s emotional well-being. However, we don’t often think about the nuances of the language we use at work. If a project team is showing signs of feeling collective inadequacy or Team Impostor Syndrome, listen to how the stakeholders of that project are interacting. There might be some tiny semantic adjustments that can help the team know that they’re the right people for the job.

This article is part of The Open Organization Guide to IT culture change.